Depression

Highlights

What Is Depression?

Clinical depression is a mood disorder in which overwhelming feelings of sadness, loss of pleasure, guilt, and hopelessness interfere with daily life. People with depression also suffer from sleep problems, difficulty concentrating, fatigue and low energy, changes in appetite, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

Types of Depression

There are different subtypes of clinical depression. They include:

- Major depression, in which at least five specific symptoms must occur for a period of at least five weeks. Episodes of major depression usually last for about 20 weeks.

- Dysthymia is chronic low-grade depression that can last for years.

- Atypical depression is characterized by the ability to temporarily experience improved mood. It is accompanied by symptoms that may include sensitivity to rejection, oversleeping, and overeating.

- Other types of depression include seasonal affective disorder, postpartum depression, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression.

American Psychiatric Association Updated Treatment Guidelines

The American Psychiatric Association's updated guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder include:

- Exercise and other healthy behaviors (good nutrition, sleep hygiene, reducing use of tobacco, alcohol, and other harmful substances) are recommended for helping improve mood symptoms.

- The guidelines recommend considering maintenance drug treatment for patients who have risk factors for depression recurrence. Maintenance treatment should definitely be offered to patients who have had more than three prior depressive episodes or chronic illness

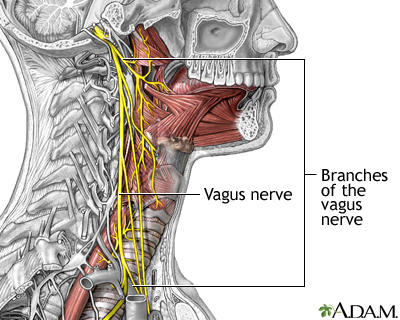

- For patients with treatment-resistant depression, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has the strongest evidence as a treatment, particularly for patients who have not been helped by medication. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation are also possible options.

Drug Approval

In 2011, the FDA approved vilazodone (Viibryd) for treatment of major depression in adults. Vilazodone is a new type of dual action selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

Introduction

Everyone experiences some unhappiness, often as a result of a life change, either in the form of a setback or a loss, or simply, as Freud said, "everyday misery." The painful feelings that accompany these events are usually appropriate and temporary, and can even present an opportunity for personal growth and improvement. However, when sadness persists and impairs daily life, it may indicate a depressive disorder. Severity, duration, and the presence of other symptoms are the factors that distinguish normal sadness from clinical depression.

Clinical depression is classified as a mood disorder. The primary subtypes are major depression, dysthymia (longstanding but milder depression), and atypical depression. Other depressive disorders include premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PDD or PMDD) and seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

The other major mood disorder is bipolar disorder, formerly called manic-depressive illness, which is characterized by periods of depression alternating with episodes of excessive energy and activity. Bipolar disorder is not discussed in this report. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #66: Bipolar disorder.]

Major Depression

Major depression is also called major depressive disorder. In major depression, at least five of the symptoms listed below must occur for a period of at least 2 weeks, and they must represent a change from previous behavior or mood. Depressed mood or loss of interest must be present. Symptoms include:

1. Depressed mood on most days for most of each day -- irritability may be prominent in children and adolescents

2. Total or very noticeable loss of pleasure most of the time

3. Significant increases or decreases in appetite, weight, or both

4. Sleep disorders, either insomnia or excessive sleepiness, nearly every day

5. Feelings of agitation or a sense of intense slowness

6. Loss of energy and a daily sense of tiredness

7. Sense of guilt or worthlessness nearly all the time

8. Inability to concentrate occurring nearly every day

9. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

In addition, other criteria must be met:

- The symptoms listed above do not follow or accompany manic episodes (such as in bipolar disorder or other disorders).

- They impair important normal functions (such as work or personal relationships).

- They are not caused by drugs, alcohol, or other substances.

- They are not caused by normal grief.

Episodes of major depression usually last about 20 weeks.

Depression in Children. Symptoms for major depression in children can differ from those in adults and may include:

- An inability to enjoy favorite activities

- Persistent sadness

- Increased irritability

- Complaints of physical problems, such as headaches and stomachaches

- Poor performance in school

- Persistent boredom

- Low energy

- Poor concentration

- Changes in eating and/or sleeping patterns

Dysthymia (Chronic Depression)

Dysthymia, or chronic depression, afflicts 3 - 6% of the general population and is characterized by many of the same symptoms that occur in major depression. Symptoms of dysthymia are less intense and last much longer, at least 2 years.

The symptoms of dysthymia have been described as a "veil of sadness" that covers most activities. Possibly because of the duration of the symptoms, patients who suffer from chronic minor depression do not exhibit marked changes in mood or in daily functioning, although they have low energy, a general negativity, and a sense of dissatisfaction and hopelessness.

Atypical Depression

About a third of patients with depression have atypical depression. Atypical depression refers to a subtype of depression characterized by mood reactivity, which is the ability to temporarily respond to positive experiences. It is accompanied by two or more associated symptoms such as sensitivity to rejection, hypersomnia (oversleeping), overeating (usually related to carbohydrate craving), and leaden paralysis (feelings of heaviness in the arms and legs).

Seasonal Affective Disorder

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is characterized by annual episodes of depression during fall or winter that improve in the spring or summer. Other SAD symptoms include fatigue and a tendency to overeat (particularly carbohydrates) and oversleep in winter. A minority of individuals with SAD have symptoms of under-eating and insomnia. SAD tends to last about 5 months in those who live in the northern part of the U.S.

Seasonal changes affect many people's moods, regardless of gender and whether or not they have SAD. Simply being mildly depressed during the winter does not mean that one has SAD. Living in a northern country with long winter nights does not guarantee a higher risk for depression. Changes in light may not be the only contributor to SAD.

Causes

The causes of depression are not fully known. Most likely a combination of genetic, biologic, and environmental factors plays a role.

Genetic Factors

Because depression often runs in families, it appears that a genetic component is involved. Studies have found that close relatives of patients with depression are two to six times more likely to develop the condition than individuals without a family history.

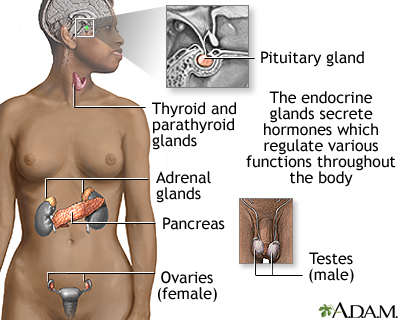

Biologic Factors

The basic biologic causes of depression are strongly linked to abnormalities in the delivery of certain key neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain). These neurotransmitters include:

- Serotonin. Perhaps the most important neurotransmitter in depression is serotonin. Among other functions, it is important for feelings of well being. Imbalances in the brain’s serotonin levels can trigger depression and other mood disorders.

- Other Neurotransmitters. Other neurotransmitters possibly involved in depression include acetylcholine and catecholamines, a group of neurotransmitters that consists of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine (also called adrenaline). Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a stress hormone and neurotransmitter, may be involved in depression and anxiety disorders.

The degree to which these chemical messengers are disturbed may be affected by other factors such as genetic susceptibility.

Reproductive Hormones. In women, the female hormones estrogen and progesterone may play a role in depression.

Environmental Factors

Medications. Many prescription drugs can affect brain chemicals and trigger depression. These medications include certain types of drugs used for acne, high blood pressure, contraception, Parkinson’s disease, inflammation, gastrointestinal relief, and other conditions.

Risk Factors

According to major surveys, major depressive disorder affects nearly 15 million Americans (about 7% of the adult population) in a given year. While depression is an illness that can affect anyone at any time in their life, the average age of onset is 32 (although adults ages 49 - 54 years are the age group with the highest rates of depression.). Other major risk factors for depression include being female, being African-American, and living in poverty.

Depression in Women

Women, regardless of nationality, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic level, have twice the rate of depression than men. (Women with depression may also have accompanying eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #49: Eating disorders.]) While men are more likely than women to die by suicide, women are twice as likely to attempt suicide.

The causes of such higher rates of depression may be due in part to hormonal factors:

- Puberty. While both boys and girls have similar rates of depression before puberty, girls have twice the risk for depression once they reach puberty. In addition to hormonal factors, sociocultural factors may also affect the development of depression in girls in this age group.

- Menstruation. While many women experience mood changes around the time of menstruation, a small percentage of women suffer from a condition called premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a specific psychiatric syndrome that includes severe depression, irritability, and tension before menstruation. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #79: Premenstrual syndrome.]

- Pregnancy and Childbirth. Hormonal fluctuations that occur during and after pregnancy, especially when combined with relationship stresses and anxiety, can contribute to depression. Post-partum depression is a severe depression (sometimes accompanied by psychosis) that occurs within the first year after giving birth. The rapid decline of reproductive hormones that accompany childbirth may play the major role in postpartum depression in susceptible women, particularly first-time mothers. Studies suggest that women who are more sensitive to hormone fluctuations are at greater risk for postpartum depression if they have a personal or family history of depression. Miscarriage also poses a risk for depression.

- Perimenopause and Menopause. Hormonal fluctuations that can trigger depression also occur when a women is transitioning to menopause (perimenopause). Sleep disruptions are also common during perimenopause and may contribute to depression. Once women pass into menopause, depressive symptoms generally tend to wane. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #40: Menopause.]

Depression in Men

Depression is not rare in men. In fact, white men over age 85 have the highest rates of suicide of any group. Men may be more likely than women to mask their depression by using alcohol. Some research suggests that depression in men is associated with the following indicators:

- Low tolerance to stress

- Behaviors such as "acting out" and being impulsive

- A history of alcohol or substance abuse

- A family history of depression, alcohol abuse, or suicide

Depression in Children and Adolescents

Depression can occur in children of all ages, although adolescents have the highest risk. Risk factors for depression in young people include having parents with depression, particularly if the mother is depressed. Early negative experiences and exposure to stress, neglect, or abuse also pose a risk for depression.

Adolescents who have depression are at significantly higher risk for substance abuse, recurring depression, and other emotional and mental health problems in adulthood.

Studies suggest that 3 - 5% of children and adolescents suffer from clinical depression, and 10 - 15% have some depressive symptoms.

Depression in the Elderly

About 1 - 5% of elderly people suffer from depression. The rate increases significantly for those who have other chronic health problems, especially medical conditions that interfere with functional abilities, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, and cancer. Depression also occurs in some elderly people who require home healthcare or hospitalization. In addition, older people often have to contend with significant stressful life changes such as the loss of a spouse. Suicide in the elderly is the third-leading cause of death related to injury. Men account for the majority of these suicides, with divorced or widowed men at highest risk.

Medical Conditions Associated with Increased Risk of Depression

Severe or Chronic Medical Conditions. Any chronic or serious illness, such as diabetes, that is life threatening or out of a person's control can lead to depression. Many medications taken for chronic medical problems can also cause depression.

Thyroid Disease. Hypothyroidism (a condition caused when the thyroid gland does not produce enough hormone) can cause depression. However, hypothyroidism may also be misdiagnosed as depression and go undetected.

Chronic Pain Conditions. Studies have reported a strong association between depression and headaches, including chronic tension-type and migraine. Fibromyalgia, arthritis, and other chronic pain syndromes are also associated with depression.

Stroke and Other Neurological Conditions. Having a stroke increases the risk of developing depression. Also, neurological conditions that impair movement or thinking are associated with depression.

Heart Failure. Patients with heart failure or patients who have suffered a heart attack may also be at increased risk for depression.

Insomnia and Sleep Disorders. Sleep abnormalities are a hallmark of depressive disorders, with many depressed patients experiencing insomnia. Likewise, insomnia or other changes in waking and sleeping patterns can have significant effects on a person's mood, and perhaps worsen or draw out an underlying depression.

Other Risk Factors

Smoking. There is a significant association between cigarette smoking and a susceptibility to depression. People who are prone to depression face a 25% chance of becoming depressed when they quit smoking, and this increased risk persists for at least 6 months. What's more, depressed smokers find it difficult to stop smoking. Smokers with a history of depression are not encouraged to continue smoking, but rather to keep a close watch on recurrence of depressive symptoms if they do stop smoking.

Complications

Depression is often chronic, with episodes of recurrence and improvement. About a third of patients with a single episode of major depression will have another episode within 1 year after discontinuing treatment, and more than half will have a recurrence at some point in their lives. Depression is more likely to recur if the first episode was severe or prolonged, or if there have been prior recurrences. To date, even newer antidepressants have failed to achieve permanent remission in many patients with major depression, although the standard medications are very effective in treating and preventing acute episodes.

Risk for Suicide

Suicidal preoccupation or threats of suicide should always be treated seriously. Depression is the cause of up to two-thirds of all suicides. Suicide attempts are a major risk factor for a later suicide. Suicide is the third most common cause of death among adolescents, and is one of the most devastating events than can happen to a family. Behavioral therapies, combined with antidepressants, may help prevent suicide. However, antidepressants can also raise the risk for suicidality (suicidal thoughts and behavior) in some young people, particularly those ages 18 - 24. [See “Suicidal Risk and Antidepressant Medications” in Drug Treatment Guidelines section in this report.]

Children, adolescents, and young adults who are prescribed antidepressant medication should be carefully monitored by both their parents and doctors, especially during the first few months of treatment, for any worsening of depression symptoms or changes in behavior.

The following are danger signs in young people:

- Withdrawal from friends

- Sudden decrease in school performance

- Loss of interest in activities that were previously pleasurable

- Unusual irritability

- Unusual changes in sleep or eating habits

Risk factors for suicide include a history of neglect or abuse, history of deliberate self-harm, a family member who committed suicide, access to firearms, and living in communities where there have been recent outbreaks of suicide among young people. A romantic break-up is often the trigger for a suicidal attempt in teenagers. Feeling connected with parents and family can help protect young people with depression from suicide.

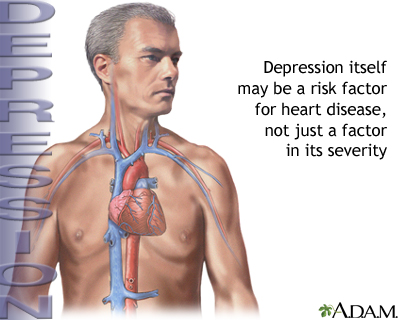

Effect on Physical Health

Major depression in the elderly or in people with serious illness may reduce survival rates, even independently of any accompanying illness. Decreased physical activity and social involvement certainly play a role in the association between depression and illness severity.

Heart Disease and Heart Attacks. Data suggest that depression itself may be a risk factor for heart disease as well as its increased severity. Patients with heart disease who are depressed tend to have more severe cardiac symptoms than those who are not depressed, and a poorer quality of life. Depression can worsen the prognosis of heart disease and increase the risk of death.

While the evidence is less conclusive, studies also indicate that depression in healthy people may increase the risk for developing heart disease. The more severe the depression, the greater the risk.

Obesity. People, especially adolescents, who are depressed have a high risk for obesity. Conversely, obese people are about 25% more likely than non-obese people to develop depression or other mood disorders.

Mental Decline. Depression in the elderly is associated with a decline in mental functioning, regardless of the presence of dementia.

Cancer. Depression does not increase the risk for cancer, but cancer can physically trigger depression by affecting chemicals in the brain. Sometimes depressive symptoms can manifest even before the cancer is diagnosed.

Impact on Daily Activities and Relationships

Effects of Parental Depression on Children. Depression in parents may increase the risk for childhood depression.

Effects on Marriage. People who suffer from psychiatric disorders tend to have higher divorce rates than healthy people. Spouses of partners with depression are themselves at higher risk for depression.

Effect on Work. Depression can adversely affect a person's work life. It significantly increases the risk for unemployment and lower income.

Substance Abuse

Alcohol and Drug Abuse. Many people with major depression also have an alcohol use disorder or drug abuse problems. Studies on the connections between alcohol dependence and depression have still not resolved whether one causes the other or if they both share some common biologic factor.

Smoking. Depression is a well-known risk factor for smoking, and many people with major depression are nicotine dependent. Nicotine may stimulate receptors in the brain that improve mood in some people with depression.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of depression is based on symptoms meeting specific criteria. [See Introduction section of this report.] Many people who are depressed first seek help from their family doctors. Guidelines recommend that family doctors screen for depression in adults and adolescents (ages 12 - 18), as long as these doctors have appropriate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of their patients.

To check if you have depression, your doctor may ask questions such as:

- Over the past month, have you felt down, depressed or hopeless?

- Over the past month, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Individuals who have certain factors might ask their doctor if they should be screened for depression. These factors include:

- Family or personal history of depression

- Multiple medical problems

- Physical symptoms that have no clear medical cause

- Chronic pain

- A need to visit doctor more frequently than expected

Screening Tests

Mental health professionals may administer a screening test such as the Beck Depression Inventory or the Hamilton Rating Scale, both of which consist of about 20 questions that assess the individual for depression. However, most mental health professionals generally diagnose depression based on symptoms and other criteria.

Symptoms of depression can vary depending on a person’s cultural and ethnic background. For example, people from non-Western countries are more apt to report physical symptoms (such as headache, constipation, weakness, or back pain) related to the depression, rather than mood-related symptoms.

Ruling Out Other Conditions

Depression can sometimes be confused with other medical illnesses. Weight loss and fatigue, for example, accompany many conditions, some serious, but they can also occur with depression.

Treatment

Depression is a treatable illness, with many therapeutic options available including psychotherapy, antidepressants, or both. In general, the treatment choice depends on the degree and type of depression and other accompanying conditions. It also may depend on age, pregnancy status, or other individual factors.

In choosing treatment options, it is important for the patient to be fully involved in the decision-making process.

Patients with Major Depression. Numerous studies support a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) plus antidepressants, typically a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). Although some people may feel better after taking antidepressants for a few weeks, most people need to take medication for at least 4 - 9 months to ensure a full response and to prevent depression from recurring. Research indicates that patients respond better to medications when drug therapy is combined with CBT. Exercise may also help relieve depressive symptoms.

Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression. For patients with severe depression who are not helped by SSRIs or SNRIs, other types of antidepressants are available. Sometimes an atypical antipsychotic drug may be given in combination with an antidepressant for patients with severe major depressive disorder.

Brain stimulation techniques, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), are options for treatment-resistant depression. Experimental procedures, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation, may be helpful. Researchers are also investigating new types of drugs (such as ketamine), which may provide rapid, if temporary, improvement. In general, the more treatment strategies that patients need, the less likely they are to recover completely from depression.

Patients with Minor Depression. Patients with minor depression (fewer than five symptoms that persist for fewer than 2 years) may respond well to watchful waiting to see if antidepressants are necessary. Counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy may be helpful, as is regular exercise.

Patients with Depression and Other Psychiatric Problems. Other psychiatric problems often coexist with depression. If patients also suffer from anxiety, treating the depression first often relieves both problems. More severe psychiatric problems, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, require specialized treatments.

Patients with Depression and Medical Conditions. Depression can worsen many medical conditions and may even increase mortality rates from some disorders, such as heart attack and stroke. Depression should be aggressively treated in anyone with a serious medical problem.

Patients with Depression and Substance Abuse Problems. Treating depression in patients who abuse alcohol or drugs is important and can sometimes help patients quit. However, absence from substance abuse is considered essential for adequate treatment of depression.

Choosing a Therapist

Most people with depression can be treated in an office setting by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other therapist. Infrequently, the level of dysfunction may be serious enough to warrant hospitalization to provide protection from further deterioration or self-harm.

Health professionals who can prescribe antidepressants include:

- Doctors, including psychiatrists

- Some nurse clinicians

Although other mental health professionals cannot prescribe drugs, most therapists have arrangements with a psychiatrist for providing medications to their patients. In general, mental health professionals are categorized by their training:

- Psychoanalysts have a degree in medicine (with additional training in psychiatry), psychology, or social work as well as several years of training at a psychoanalytic institute.

- Psychologists have received a Ph.D, including an internship in a mental healthcare facility.

- A clinical social worker has a master's degree and 2 years of supervised experience in mental health and human services.

- Advanced-practice psychiatric nurses have a master's degree and can provide therapeutic services.

Tips for selecting a therapist:

- Patients can locate a mental health professional in their area by asking their doctor for a referral or by contacting a mental health organization. [See Resources section of this report.]

- The patient should describe problems briefly but specifically over the phone to any prospective therapist to get a sense of whether he or she will suit the patient's needs.

- Patients should not be shy about considering a change in their therapist if they lack confidence in their current one.

Treating Depression During and After Pregnancy

Up to a quarter of women experience depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and some women develop full-blown postpartum depression following delivery. Although a mother's depression during and after pregnancy can have serious effects on her child, researchers are still trying to determine the best methods for preventing and treating pregnancy-related depression.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that pregnant women with depression receive care from a multidisciplinary team that includes the patient’s obstetrician, primary care physician, and mental health clinician. Any woman who has suicidal or psychotic symptoms during depression should immediately seek treatment from a psychiatrist.

The use of antidepressants during pregnancy is controversial, especially for women with major depression who regularly take antidepressant medication. Most doctors advise women to avoid, if possible, any medications during pregnancy and nursing. But women with depression who stop taking antidepressants during pregnancy may be likely to have a relapse of depression, which can have negative consequences for prenatal care and subsequent mother-child bonding. The risks for negative outcomes are highest when depression occurs during the late second or early third trimester. Depression during pregnancy may also increase the risk of developing postpartum depression.

ACOG and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommend that women who are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant should not stop taking antidepressants without first talking to their doctors. Women who have mild or no depressive symptoms for at least 6 months before becoming pregnant may be able to taper off or discontinue antidepressant medication, under supervision of their doctor. Stopping medication may be more difficult for women with a history of severe recurrent depression. Psychotherapy (preferably cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy) may be helpful in addition to, or in replacement of, antidepressant medication. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be an option for pregnant women with severe depression.

Studies have been inconsistent as to whether serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) drugs increase the risk for birth defects. In general, the risks appear to be low, but doctors are still not sure. There is evidence that paroxetine (Paxil, generic) may cause major birth defects -- including heart abnormalities -- if taken during the first trimester of pregnancy. ACOG recommends that doctors not prescribe paroxetine to women who are pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant. Some studies have indicated that sertraline (Zoloft, generic) and citalopram (Celexa, generic) may also increase the risk of heart defects. SSRIs, and most tricyclic antidepressants, are considered safe to use during breastfeeding but more research is needed to clarify the effects of SSRI on infant and child development. [For more information, see "Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)" in Medications section.]

In terms of non-drug treatment of postpartum depression, doctors recommend that women with signs of postpartum depression receive intensive and individualized psychotherapy within a month after giving birth.

Treating Depression in the Elderly

Some doctors recommend only psychotherapy for elderly patients with mild depression. In many older patients, a regular exercise program may be sufficient to improve mood. The use of antidepressants in the elderly is problematic:

- Tricyclics are as effective as and less expensive than SSRIs, but they have more side effects. Specifically, they pose a higher risk for adverse effects on the heart and possibly the lungs. (The older tricyclics, such as amitriptyline and imipramine, have other severe side effects in older adults.)

- SSRIs have fewer side effects than tricyclics. However, SSRIs may not pose any lower risk for falls than the older tricyclic antidepressants. In addition, researchers are investigating whether SSRIs are associated with an increased rate of osteoporosis (“thin bones”) and hip fractures in older adults.

Treating Depression in Children and Adolescents

Studies suggest that when children or adolescents are treated for depression, most recover. Still, up to a half of these young people have a recurrence of depression within 2 years of their first episode of depression.

It is important to recognize that childhood depression differs from adult depression and that children may respond differently than adults to antidepressant medication. These variances are due to childhood brain development processes as well as age-related differences in drug metabolism. Children may experience medication side effects not seen in adults, and some antidepressants that are effective for adults may not work for children.

Mild-to-Moderate Depression. The pediatrician may want to monitor a child with mild depression for 6 - 8 weeks before deciding whether to prescribe psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or a referral to a mental health professional. Once medication has been started, the doctor will decide if the dosage needs to be increased after another 6 - 8 weeks. Medication may need to be continued for 1 year after the symptoms have resolved, and the doctor should continue to monitor the child on a monthly basis for 6 months after full remission of depression. For psychotherapy, cognitive therapy may be the best approach for children and adolescents with depression. Other types of psychotherapy, such as family therapy and supportive therapy, may also be effective.

Severe Depression. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends an SSRI antidepressant for children and adolescents with very severe depression that does not respond to psychotherapy. Tricyclic antidepressants do not tend to help adolescents and children and these drugs have many side effects. MAOIs are also not commonly prescribed.

Many SSRIs appear to be safe and effective, but at this time fluoxetine (Prozac, generic) and escitalopram (Lexapro) are the only ones approved for adolescents (ages 12 - 17), and fluoxetine is the only antidepressant approved for children age 8 and older. The FDA strongly advises against the use of some specific SSRIs, such as paroxetine (Paxil, generic), due to concerns about an increased risk for suicidal behavior as well as the lack of any evidence supporting the drug's efficacy in pediatric patients. Some recent research indicates that the overall benefits of antidepressants for children and adolescents may outweigh the risks for suicidal behavior. For optimal results, SSRIs should be combined with either cognitive-behavioral or interpersonal psychotherapies.

Due to potential suicide risks, children and adolescents should be monitored regularly during the initial months of antidepressant treatment. [For more detailed information, see "Suicide Risk and Antidepressant Medications" in Drug Treatment Guidelines section of this report.]

Drug Treatment Guidelines

Major Classes of Antidepressants and General Treatment Guidelines

Major classes of antidepressants include:

- Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These drugs have become the standard antidepressants. They target the brain chemical (neurotransmitter) serotonin. They can be effective and usually have moderate side effects.

- Other neurotransmitter inhibitors. These drugs target neurotransmitters other than or in addition to serotonin, such as norepinephrine. Many are proving to be effective in patients who do not respond to standard antidepressants or in specific patients, such as smokers who want to quit or patients with chronic pain.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). These drugs are effective but can have severe adverse effects, particularly in older people.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). These drugs include newer selective MAOIs. MAOIs are the most effective antidepressants for atypical depression, but have some severe side effects and require restrictive dietary rules and care to avoid drug interactions.

All of these drugs appear to work equally well, although they may vary in terms of side effects. Your doctor will select an antidepressant based on side effects, cost, and your personal preference.

Approach and Duration of Initial Treatment. The guidelines for the duration of an initial antidepressant regimen are generally:

- Patients should start at a low dose, which is increased over a period of 5 - 10 days.

- Patients should see their doctor every 1- 2 weeks until substantial improvement occurs. It may take 4 - 8 weeks before a patient experiences the effects of any antidepressant.

- Side effects usually diminish within 1 - 4 weeks. (Exceptions may be weight gain and sexual dysfunction.)

- If no improvement occurs within 6 - 8 weeks of starting drug treatment, the doctor may either increase the dosage or switch to an alternative drug. More than 80% of patients respond to some antidepressant, although specific drugs are helpful for only about half of patients. This suggests that if one medication fails, another has a good chance of being helpful. In general, the fewer drug treatment strategies required, the better a patient's chances of recovering completely from depression. Patients who become symptom-free have the best chance for complete recovery compared to patients whose symptoms merely improve.

- In general, patients should continue taking antidepressants for at least 4 - 9 months after symptom relief to help prevent relapse. Patients who have had at least 2 episodes of depression may need to continue drug treatment for longer than 9 months. (Patients who improve within 2 weeks of taking medications may not require lengthy treatment.)

Treating Recurrence. Recurrence of depression is very common. About a third of patients will relapse after a first episode within a year of ending treatment, and more than half will experience a recurring bout of depression at some point during their lives. Among those at highest risk for early relapse and who may require ongoing antidepressants are:

- Patients with at least two episodes of major depression or major depression that lasts for 2 years or longer before initial treatment.

- Patients who continue to have low-level depression for 7 months after starting antidepressant treatments.

- Patients may need maintenance therapy. The American Psychiatric Association recommends considering maintenance therapy for patients who are have risk factors for depression recurrence. Patients who have experienced more than three prior depressive episodes, or who have chronic illnesses, should definitely be given maintenance therapy. Doctors disagree, however, on the optimal length or the appropriate dosage of maintenance therapy.

There is no risk for addiction with current antidepressants, and many of the common antidepressants, including most standard SSRIs, have been proven safe when taken for a number of years.

Common Side Effects of Most Antidepressants. No matter how well a drug treats depression, the ability of patients to tolerate its side effects strongly influences their compliance with therapy. Side effects can be avoided or moderated if any regimen is started at low doses and built up over time. Although specific side effects are discussed under individual drugs, there are a few that are common to many of them:

- Sexual dysfunction is a common side effect of many of the standard antidepressants and some of the newer drugs. Some antidepressants, such as bupropion (Wellbutrin, generic), do not pose as high a risk for this problem. PDE5 inhibitor drugs [sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis)], used for erectile dysfunction in men, may help improve sexual dysfunction. However, they do not increase the sex drive (libido).

- An increased risk of oral health problems caused by dry mouth is associated with long-term use of many antidepressants, particularly tricyclics. Patients can increase salivation by chewing gum, using saliva substitutes, and rinsing the mouth frequently.

- Virtually all antidepressants have complicated interactions with other drugs; some are very important. Patients should inform the doctor of any drugs they are taking, including over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies.

- Nearly all antidepressants are metabolized in the liver, so anyone with liver abnormalities should use them with caution.

- Abrupt withdrawal from many antidepressants can produce severe side effects; no antidepressant should be stopped abruptly without consultation with a doctor. To avoid withdrawal symptoms, it is best to gradually taper off antidepressants rather than discontinue them abruptly.

Suicide Risk and Antidepressant Medications

In recent years, there has been concern that SSRI antidepressants can increase the risk for suicidal behavior. Of particular concern is a greater risk for suicide in young people taking these medications. While depression is itself the major risk factor for suicide, and antidepressant medication may revitalize suicidal attempts in patients who were too despondent before treatment to make the effort, evidence suggests that in some cases the medication itself can cause suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality). Paroxetine (Paxil, generic) appears to have the strongest association with increased suicidal risk, particularly in younger adults.

In the U.S., all antidepressant medications now carry “black box” warnings on their prescribing label explaining the association between antidepressant use and increased risk for suicidality in children, adolescents, and young adults ages 18 - 24, especially during the first few months of treatment. The FDA’s data do not show an increased risk for suicidality in adults older than age 24. Adults age 65 years and older taking antidepressants have a decreased risk for suicidality.

The FDA recommends that caregivers monitor children, adolescents, and young adults being treated with antidepressants for sudden behavioral changes, and immediately notify their doctor if such changes occur. These behavioral signs include:

- Agitation

- Irritability

- Anxiety

- Panic attacks

- Insomnia

- Aggressiveness

- Impulsivity

- Hyperactivity in actions and speech

- Worsening of depression

- Increased thoughts of suicide

The FDA’s guidelines for medication usage also recommend that all patients see their doctors regularly after initiating drug treatment. The recommended schedule is:

- Once per week for 4 weeks (1st month)

- Every 2 weeks for the next month (2nd month)

- At the end of week 12 following the start of drug treatment (3rd month)

- More frequently if changes in mood or behavior occur

- Patients should also be closely monitored if their drug dosage is changed.

Patients should immediately contact their doctor if depression symptoms worsen or if suicidal thoughts or behavior increase.

Medications

Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line treatment for major depression. They work by increasing levels of serotonin in the brain. Because they act specifically on serotonin, SSRIs have fewer side effects than older antidepressants, which have more widespread effects in the body.

SSRIs include fluoxetine (Prozac, generic), sertraline (Zoloft, generic), paroxetine (Paxil, generic), fluvoxamine (Luvox, generic), citalopram (Celexa, generic), and escitalopram (Lexapro). There do not appear to be significant differences among SSRI brands in effectiveness, although individual drugs may have different side effects or benefits for specific patients.

At this time, fluoxetine and escitalopram are the only antidepressants approved for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents (ages 12 - 17). Fluoxetine is also approved for children age 8 and older.

Candidates for SSRIs. SSRIs appear to best help people with the following conditions:

- Mild-to-moderately severe major depression

- Seasonal affective disorder

- Dysthymia

- Severe premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). A repackaged form of fluoxetine (Sarafem) is the first SSRI specifically FDA-approved for PMDD. Other SSRIs and newer antidepressants are also proving to be effective.

- Anxiety disorders

- Bulimia

Duration of Effectiveness and Use. SSRIs take, on average, 2 - 4 weeks to be effective in most adults. They may take even longer, up to 12 weeks, in the elderly and in those with dysthymia. By 14 weeks, depression should be in remission in those who respond to the drugs. Unfortunately, recurrence is common once the drugs are stopped. Studies indicate that the standard SSRIs are generally safe to be taken long term, although it is still unclear which patients most benefit from on-going medication. Some doctors recommend withdrawing from medication after a year. If depression recurs, then the patient should go back on the antidepressant.

Side Effects of SSRIs. Side effects may include:

- Nausea and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, which usually wear off over time.

- Insomnia or drowsiness, depending on the drug

- Agitation and nervousness

- Dry mouth

- Headache

- Heart palpitations

- Weight gain varies depending on the SSRI.

- Sexual side effects may include delayed or loss of orgasm and low sexual drive. Paroxetine may cause heart-related birth defects if taken during the first 3 months of pregnancy. The most common heart abnormalities are ventricular septal defects, which are holes in the muscular wall that separate the main pumping chambers of the heart. Pregnant women who are being treated for major depression should not stop taking antidepressants without first talking to their doctors. [For more information on antidepressant treatment guidelines during pregnancy, see "Treating Depression During and After Pregnancy" in Treatment section.]

- SSRIs can worsen manic symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder.

Drug Interactions. SSRIs can interact with other antidepressants such as tricyclics and, in particular, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Due to a potentially fatal condition called serotonin syndrome, SSRIs should never be taken in combination with an MAOI or within 2 weeks after discontinuing MAOI treatment. (For more on serotonin syndrome, see MAOI section below.) Other serious interactions can occur with meperidine (Demerol, generic) and illegal substances (such as LSD, cocaine, or ecstasy). SSRIs also interact with the antibiotic linezolid (Zyvox), the painkiller tramadol (Ultram, generic), and the osteoporosis medication raloxifene (Evista). People who take SSRIs may drink alcohol in moderation, although the combination may compound any drowsiness experienced with SSRIs, and some SSRIs increase the effects of alcohol.

Withdrawal Symptoms. Cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, increase in depressive symptoms, and electric shock-like symptoms can occur with sudden discontinuation of SSRIs. The symptoms are more likely to occur with antidepressants with shorter half-lives as compared with fluoxetine, which has a long half-life. The dose of the antidepressant should be slowly reduced before stopping.

Other Neurotransmitter Inhibitors

These antidepressants target other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine or dopamine, alone or in addition to serotonin.

Dual Action Inhibitors. Dual action inhibitors act directly on serotonin and another neurotransmitter.

Venlafaxine (Effexor, generic), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and mirtazapine (Remeron) are serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). They target serotonin and the neurotransmitter norepinephrine and are approved for treatment of major depression in adults.

Vilazodone (Viibryd) is a new type of dual action inhibitor that acts both as an SSRI and as a 5-HT1-A receptor partial agonist. It was approved in 2011 for treatment of depression in adults.

These drugs share many of the side effects as SSRIs, including dry mouth, nausea, and drowsiness. Additional side effects include:

- Venlafaxine (Effexor, generic) and desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) are chemically related. These drugs can increase blood pressure and heart rate and should be used with caution in patients with high blood pressure or heart disease. They can also cause uterine and vaginal bleeding unrelated to menstruation. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine should not be taken during the last trimester of pregnancy as they can cause complications in newborn infants. Some patients report severe withdrawal symptoms, including dizziness and nausea.

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta) can worsen narrow-angle glaucoma and liver or kidney problems. Because duloxetine can cause liver damage, patients who drink large quantities of alcoholic beverages should not take it. Signs of liver damage include itching, dark urine, yellowing of skin and eyes (jaundice), and fatigue. Patients should immediately contact their doctor if they experience these symptoms.

- Mirtazapine (Remeron) can cause impulsivity, panic attacks, and restlessness.

Multiple Neurotransmitter Inhibitors (Bupropion). Bupropion (Wellbutrin, generic) affects the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine -- a third important neurotransmitter. In addition to depression, bupropion is also approved for treating seasonal affectiveness disorder (SAD) and, under the tradename Zyban, for smoking cessation. Bupropion causes less sexual dysfunction than SSRIs. About 25% of patients experience initial weight loss. Side effects include restlessness, agitation, sleeplessness, headache, and stomach problems. Bupropion has a risk for seizures, which increases with higher doses. High doses may also cause dangerous heart arrhythmias.

In 2009, the FDA warned that bupropion products may cause symptoms such as changes in behavior, hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and attempted suicide. Most of these symptoms were reported in patients who took bupropion to help stop smoking. However, the FDA also warns that patients who have major depressive disorder or other psychiatric illnesses (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), may experience worsening of their symptoms while taking bupropion

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Before the introduction of SSRIs, tricyclics were the standard treatment for depression.

Tricyclics are sometimes grouped into two categories:

- Tertiary amines include amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep, generic) and imipramine (Tofranil, generic).

- Secondary amines include desipramine (Norpramin, generic) and nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl, generic). Secondary amines may have fewer side effects, including drowsiness, than tertiary amines, but they are as toxic in high amounts.

Less commonly used tricyclics include doxepin (Sinequan), amoxapine (Asendin), maprotiline (Ludiomill), protriptyline (Vivactil), and trimipramine (Surmontil). These are all available as generics.

Tricyclics are as effective for treating depression but they have many side effects. They may offer benefits for many people with dysthymia, who generally do not respond to SSRIs. They may also be prescribed in lower dosages to be taken at night to help with insomnia.

Side Effects of Tricyclics. Side effects are common with these medications. In an analysis of studies, more tricyclic users discontinued their drugs due to side effects than did SSRI or MAOI users. Side effects most often reported include:

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Blurred vision

- Sexual dysfunction

- Weight gain

- Difficulty urinating

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness -- blood pressure may drop suddenly when sitting up or standing.

Tricyclics can have serious, although rare, side effects:

- They tend to cause disturbances in heart rhythm, which can pose a danger for some patients with certain heart diseases. Care should be taken when these medications are prescribed to the elderly and to those at risk of overdose. In particular, desipramine (Norpramin, generic) has been associated with dangerous heart rhythm abnormalities in patients who have a family history of these problems.

- Tricyclics, particularly imipramine, may increase the risk for a lung disease called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which can cause lung inflammation and scarring. Initial symptoms are breathlessness and dry cough.

- Tricyclics can be fatal with an overdose.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) block monoamine oxidase, an enzyme which has negative effects on many of the neurotransmitters that are important for well-being. MAOIs include phenelzine (Nardil, generic), isocarboxazid (Marplan, generic), and tranylcypromine (Parnate, generic).

Newer MAOIs, such as selegiline (Eldepryl, Movergan, generic), target only one form of the MAOI enzyme. They may cause fewer side effects than older MAOIs. A skin patch form of selegiline (Emsam) is also available for treatment of major depressive disorder in adults.

Candidates for MAOIs. Because these drugs can have very severe side effects, they are usually prescribed only for severe depression or when other types of antidepressants do not help (treatment-resistant depression). MAOIs may also be effective for the following conditions:

- Atypical depression

- Eating disorders

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Borderline personality

Side Effects. MAOIs commonly cause the following side effects:

- Orthostatic hypotension (a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing)

- Drowsiness or insomnia

- Dizziness

- Sexual dysfunction

- The most serious side effect is severe hypertension (high blood pressure), which can be brought on by eating certain foods having high tyramine content. Such foods include aged cheeses, most red wines, sauerkraut, vermouth, chicken livers, dried meats and fish, canned figs, fava beans, and concentrated yeast products.

- MAOIs can cause birth defects and should not be taken by pregnant women.

Serotonin Syndrome. Serotonin syndrome is a potentially fatal condition that can occur from interactions with other antidepressants, including SSRIs. Symptoms include confusion, agitation, sweating and shivering, and muscle spasms. There should be at least a 2-week break between taking MAOIs and other antidepressants. MAOIs can have serious interactions with other drugs as well, including some common over-the-counter cough medications. In such cases, severe high blood pressure or dangerous reactions can occur. It is important that patients discuss with their doctors any other medications they are taking.

Atypical Antipsychotics

If patients fail to respond to antidepressants, doctors may try adding on a different type of drug. (This combination strategy is called “augmentation” or “adjunctive treatment”.) Atypical antipsychotics are drugs that are usually prescribed for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, but they can also play a role in the treatment of severe depression. Two atypical antipsychotics, aripiprazole (Abilify) and quetiapine (Seroquel), are currently approved in combination with antidepressant therapy for treatment of adults with major depressive disorder.

Investigational Drugs

Ketamine. Ketamine, an anesthetic drug, may be helpful for patients with severe treatment-resistant or bipolar depression. In preliminary studies a single intravenous dose of ketamine helped patients quickly recover from depression within 2 hours, and some patients sustained benefits for up to a week. (Standard antidepressant drugs usually take about 8 weeks to have an effect.) Ketamine blocks the NMDA brain protein receptor, which is involved in glutamate regulation. Glutamate is a brain chemical that is thought to be involved in depression.

Psychotherapy

Among the various psychotherapeutic "talk therapies," cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to be the most effective approach. If psychotherapy is used alone without medications, benefits should be evident within 8 weeks and symptoms should be fully resolved by 12 weeks. If these conditions are not met, then the patient should strongly consider antidepressant drugs.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

For many patients, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) works as well as antidepressants in treating severe depression. Like all psychotherapies, much of the success depends on the skill of the therapist. Many studies suggest that combining cognitive therapy with antidepressants offer the greatest benefits. Studies also indicate that the benefits of cognitive therapy persist after treatment has ended.

Best Candidates. Although helpful for all patients with depression, CBT may be particularly helpful for the following patients:

- Patients with atypical depression or dysthymia

- Patients with a history of suicidal behavior

- Adolescents with mild symptoms of major depression

- Women with non-psychotic postpartum depression

- Children of parents with the depression -- in this case, therapy should involve the whole family.

Approach. CBT focuses on identification of distorted perceptions that patients may have of the world and themselves, on changing these perceptions, and on discovering new patterns of actions and behavior. These perceptions, known as schemas, are negative assumptions developed in childhood that can precipitate and prolong depression. CBT works on the principle that these schemas can be recognized and altered, thereby changing the response and eliminating the depression.

- First, the patient must learn to recognize depressive reactions and thoughts as they occur, usually by keeping a journal of feelings about, and reactions to, daily events.

- The patient is often given "homework" that tests old negative assumptions against reality and demands different responses.

- Then, the patient and therapist examine and challenge these entrenched and automatic reactions and thoughts.

- As patients begin to understand that the beliefs and assumptions that cause depression are incorrect, they can begin substituting new, positive ways of coping.

Over time, such exercises help build confidence and eventually alter behavior. Patients may take group or individual cognitive therapy. CBT is a time-limited treatment, typically lasting 12 - 14 weeks.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

Interpersonal therapy, which is related to psychodynamic therapy, acknowledges the childhood roots of depression, but focuses on symptoms and current issues that may be causing problems. IPT is not as specific as cognitive or behavioral therapy, and all work is done during the sessions. The therapist seeks to redirect the patient's attention, which has been distorted by depression, toward the daily details of social and family interaction. The goals of this treatment method are improved communication skills and increased self-esteem within a short period of time (3 - 4 months of weekly appointments). Among the forms of depression best served by IPT are those caused by distorted or delayed mourning, unexpressed conflicts with people in close relationships, major life changes, and isolation.

Supportive Psychotherapy or Attention Intervention

The intent of supportive psychotherapy or attention intervention is to provide the patient with a nonjudgmental environment by offering advice, attention, and sympathy. Supportive therapy may be particularly helpful for improving compliance with medications by giving reassurance, especially when setbacks and frustration occur.

Other Treatments

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is commonly called shock treatment. It has received bad press, in part for its potential memory-depleting effect. Since its introduction in the 1930s, ECT has been significantly refined, and is now considered an effective and safe treatment for severe depression in the appropriate situation. It is especially effective for patients who have not been helped by medication and those with severe depression who experience delusions and hallucinations. Maintenance ECT may also help prevent relapse.

Candidates for ECT. ECT may be helpful for the following patients with severe depression:

- Patients who cannot take antidepressant drugs or who have not been helped by drug therapy

- Patients with major depression with psychotic or catatonic features

- Suicidal patients

- Elderly patients who are psychotic and depressed

- Pregnant women with severe depression

- Young patients who fit the adult criteria for ECT

The Procedure. In general, hospitalization is not necessary. ECT involves the following steps:

- The patient receives a muscle relaxant and short-acting anesthetic.

- A small amount of electric current is sent to the brain, causing a generalized seizure that lasts for about 40 seconds.

- Most patients receive 6 treatments, spaced every 2 - 5 days. Others receive up to 15 treatments, followed by 6 - 12 additional treatments spaced every other week or longer for another 2 - 4 months.

Side Effects. Side effects of ECT may include temporary confusion, memory lapses, headache, nausea, muscle soreness, and heart disturbances. Concerns about permanent memory loss appear to be unfounded.

The ECT procedure affects heart rate and blood pressure. Doctors should perform a medical evaluation of patients before they receive ECT. Patients, (especially those who are elderly), who have high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, asthma, or other heart or lung problems may be at increased risk for heart-related side effects.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Deep Brain Stimulation

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) uses high frequency magnetic pulses that target affected areas of the brain. It is generally regarded as a second line treatment after ECT. Researchers are continuing to refine rTMS techniques to attempt to improve treatment outcomes.

An implantable deep brain stimulation device (Reclaim), similar to a pacemaker and devices used for treating movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease, has been approved for treatment of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. It is currently in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. The device uses four electrodes that are surgically implanted into the brain and connected to a small generator that is implanted near the abdomen or collar bone. The generator delivers precisely controlled electrical pulses to target specific areas of the brain.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a procedure that is effective for certain patients with epilepsy, and is now showing some success in patients with treatment-resistant depression

VNS involves implanting a battery-powered device under the skin in the upper left of the chest. The neurologist programs the device to deliver mild electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve. The two vagus nerves are the longest nerves in the body. They run along each side of the neck, then down the esophagus to the gastrointestinal tract. The vagus nerve travels to areas of the brain that control functions such as sleep and mood.

Studies report response rates of 35 - 46% in appropriate candidates with treatment-resistant depression. VNS is approved by the FDA for long-term treatment of chronic depression in adults who have not responded to typical treatments for their major depressive episode. Patients who use VNS may continue to show improvement in both their depression symptoms and quality of life.

Vagal stimulation can cause shortness of breath, hoarseness, sore throat, coughing, ear and throat pain, or nausea and vomiting. These side effects can be reduced or eliminated by reducing the intensity of stimulation. Long-term studies on patients with epilepsy have reported no serious adverse side effects, although the treatment may cause lung function deterioration in some people with existing lung disease.

Phototherapy (Light Therapy)

Phototherapy, also called light therapy, may be recommended as treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), particularly for patients who do not wish to use antidepressants.

The procedure is noninvasive and simple. It is best performed immediately after waking in the morning. The patient sits a few feet away from a box-like device that emits very bright fluorescent light (10,000 lux) for about 30 minutes every day.

Some people report mood improvement as early as 2 days after treatment. In others, depression may not lift for 3 - 4 weeks. If no improvement is experienced after that, depressive symptoms will be unlikely to respond to phototherapy. Phototherapy may work best when combined with cognitive behavioral therapy.

Side Effects. Side effects include headache, eye strain, and irritability, although these symptoms tend to disappear within a week. Patients taking light-sensitive drugs (such as those used for psoriasis), certain antibiotics, or antipsychotic drugs should not use light therapy. Patients should be examined by an ophthalmologist before undergoing this treatment.

Lifestyle Changes

Exercise and Other Healthy Behaviors

Exercise. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training can help provide some improvement in mood symptoms for patients with depression. Aerobic workouts can raise chemicals in the brain, such as endorphins, adrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine that produce the so-called runner's high. Yoga practice, which involves rhythmic stretching movements and breathing, may help improve and stabilize mood. Meditation may also be helpful.

Sleep Hygiene. Patients with depression who suffer from insomnia (either as a result of the condition or medications) may be helped by learning sleep hygiene techniques. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #27: Insomnia.]

Nutrition and Diet. A healthy diet low in saturated foods and rich in whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables is important for anyone. Patients should be sure to maintain a regular healthy diet, particularly if they have experienced weight gain from medications. They should also try to decrease their use of alcohol and tobacco.

Social Support. A strong network of social support is important for both prevention and recovery from depression. Support from family and friends must, however, be healthy and positive. It is helpful for family members to become educated about depression and antidepressant medications.

Herbal Remedies and Dietary Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

St. John's wort. St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) is probably the most studied herbal remedy. Although its efficacy has not been proven, there is evidence it may help some patients with mild-to-moderate depression. It does not appear to help patients with severe depression.

The following guidelines are recommended:

- People with depression should not use St. John's wort without consulting a doctor. Children and pregnant or nursing women should not take this substance.

- Although no specific dose levels have been established, evidence suggests taking 900 mg daily (300 mg taken 3 times a day or 450 mg taken twice a day).

- It takes between 2 - 3 weeks for the herb to have an effect.

- St. John's wort should not be combined with other antidepressants. This herb may also interact with other types of medications and increase or decrease their potency. St. John's wort can increase the risk for bleeding when used with blood-thinning drugs. It can also reduce the strength of certain drugs including those used for cancer and HIV treatments.

Side effects are uncommon but may include nausea, dry mouth, allergic reactions, and fatigue. This herb may increase sensitivity to light (photosensitivity).

SAM-e. S-adenosyl methionine, better known as SAM-e, is a molecule found in the human body and is involved in the processing of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin. Studies have shown that levels of SAMe are lower in patients with severe major depressive disorder. Some studies have indicated that SAM-e dietary supplements may be helpful for patients with depression, but more data are needed.

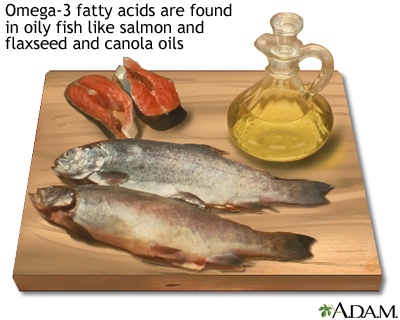

Fish Oil. Some studies have suggested omega-3 fatty acids may be helpful for depression Omega-3 fatty acids are found in fish oil, canola oil, soybeans, flaxseed, and certain nuts and seeds. Their main chemical compounds -- eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) – are also available in combination dietary supplement form. Some research has suggested that the Mediterranean Diet, which is high in omega-3 rich foods as well as vegetables and fruit and low in saturated fats from meat, may help reduce the risk of developing depression.

Vitamins. Certain B vitamins may be associated with some protection against depression.

- Vitamin B-3 (niacin) is important in the production of tryptophan and is produced from processing vitamin B3 (niacin). Dietary sources of niacin include oily fish (such as salmon or mackerel), pork, chicken, dried peas and beans, whole grains, seeds, and dried fortified cereals.

- Vitamin B-12 and calcium supplements may possibly help reduce depression that occurs before menstruation.

- Low levels of folate, a B vitamin, may be associated with depression. Researchers are studying whether folate supplements may help enhance the effectiveness of SSRIs and other antidepressants. The American Psychiatric Association notes that folate supplements carry little risk (and can help prevent birth defects), and it may be reasonable for patients to take folate along with drug therapy.

Acupuncture

Some small studies have suggested that acupuncture may help in relieving depression. Larger studies are needed to confirm its benefits. Based on the current evidence, it does not appear that acupuncture is helpful for major depression.

Resources

- www.nimh.nih.gov -- National Institute of Mental Health

- www.dbsalliance.org -- Depression and Bipolar Support Association

- www.parentsmedguide.org -- American Psychiatric Association-sponsored information on pediatric antidepressants

- www.nami.org -- National Alliance on Mental Illness

- www.nmha.org -- Mental Health America

- www.psych.org -- American Psychiatric Association

- www.apa.org -- American Psychological Association

- www.aacap.org -- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- www.postpartum.net -- Postpartum Support International

- www.mentalhealth.samhsa.gov -- National Mental Health Information Center

References

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists number 92. Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):1001-20.

Adams SM, Miller KE, Zylstra RG. Pharmacologic management of adult depression. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Mar 15;77(6):785-92.

Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun 28;356(26):2684-92.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter on the use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;48(9):961-73.

American Psychiatric Association, Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: third edition. American Psychiatric Association; Oct 2010.

Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):55-68.

Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007 Apr 18;297(15):1683-96.

Cassano P, Fava M. Mood disorders: major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Biederman J, Rauch SL, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:chap 29.

Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE; GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):e1313-26.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Feb 28;373(9665):746-58.

Cuijpers P, Geraedts AS, van Oppen P, Andersson G, Markowitz JC, van Straten A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 Jun;168(6):581-92. Epub 2011 Mar 1.

Fortinguerra F, Clavenna A, Bonati M. Psychotropic drug use during breastfeeding: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2009 Oct;124(4):e547-56. Epub 2009 Sep 7.

Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010 Jan 6;303(1):47-53.

Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Dec 6;155(11):772-85.

Janicak PG, O'Reardon JP, Sampson SM, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, Rado JT, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a comprehensive summary of safety experience from acute exposure, extended exposure, and during reintroduction treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;69(2):222-32.

Kellner CH, Knapp RG, Petrides G, et al. Continuation electroconvulsive therapy vs pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in major depression: a multisite study from the Consortium for Research in Electroconvulsive Therapy (CORE). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;63(12):1337-44.

Lin PY, Su KP. A meta-analytic review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 Jul;68(7):1056-61.

Little A. Treatment-resistant depression. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Jul 15;80(2):167-72.

March JS, Vitiello B. Clinical messages from the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS). Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Oct;166(10):1118-23. Epub 2009 Sep 1.

O'Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Gaynes BN. Screening for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):793-803.

Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, Zlotnick C. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;200(4):357-64.

Qaseem A, Snow V, Denberg TD, Forciea MA, Owens DK; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of American College of Physicians. Using second-generation antidepressants to treat depressive disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Nov 18;149(10):725-33.

Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Majem LS, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Oct;66(10):1090-8.

Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, Levenson M, Holland PC, Hughes A, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2009 Aug 11;339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880.

Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 Sep 6. [Epub ahead of print]

Tess AV, Smetana GW. Medical evaluation of patients undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 2;360(14):1437-44.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2009 Apr;123(4):1223-8.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):784-92.

Williams SB, O'Connor EA, Eder M, Whitlock EP. Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2009 Apr;123(4):e716-35.

Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;114(3):703-13.

Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE, Laraque D; GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):e1299-312.

|

Review Date:

2/8/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |